The Colorado River water management crisis has reached another critical moment.

There is a deadline on the wall, and the West just missed it.

February 14th came and went without agreement among the seven Colorado River Basin states on how to manage one of the most critical water systems in North America. It wasn’t the first missed deadline. It likely won’t be the last. But with each passing month, the stakes get higher, the reservoirs get lower, and the consequences for communities, agriculture, and water managers across the West grow more serious.

For irrigation professionals, contractors, and anyone who depends on a reliable water supply in the American West, what happens next with the Colorado River is not a political abstraction. It’s a practical reality that will shape how water is allocated, priced, and managed for decades to come.

The Problem in Plain Terms

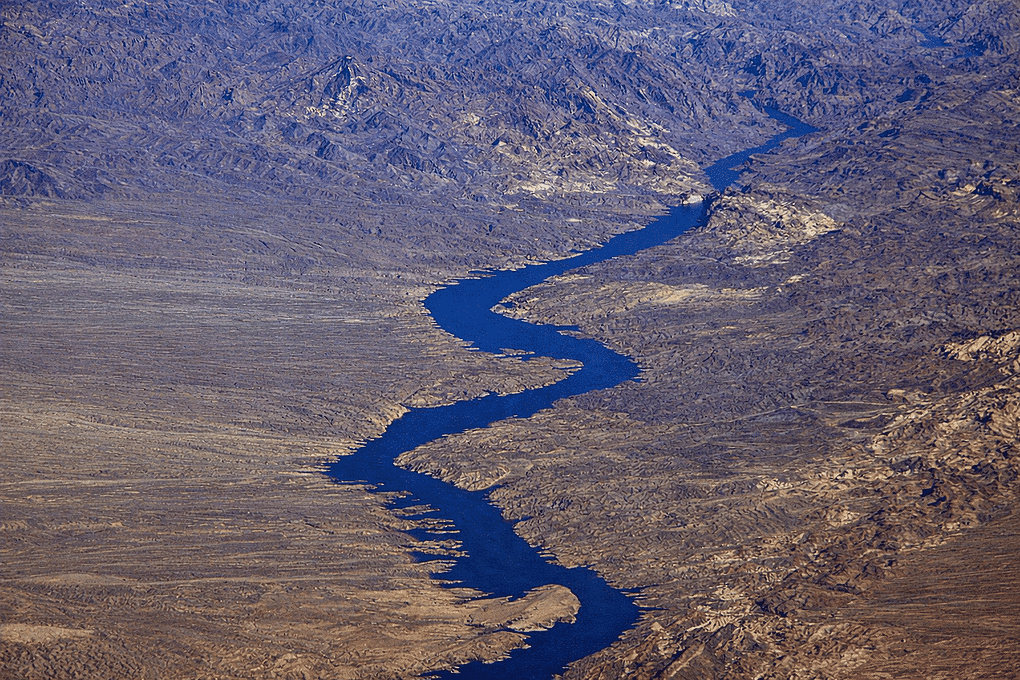

The Colorado River supplies water to roughly 40 million people across seven states: Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. It also serves 30 tribal nations and supports irrigated agriculture throughout the region. The current rules for storing and sharing this water expire this fall.

The negotiations focus mainly on two massive reservoirs: Lake Powell and Lake Mead, which are the largest in the country. Both have dropped to historic lows in recent years. Since January, projected water inflow into Lake Powell has fallen by 1.5 million acre-feet, or roughly 488 billion gallons, wiping out what would otherwise seem like a cushion heading into spring.

JB Hamby, Colorado’s top negotiator, summed it up bluntly: “Our real issue is not that we’ve run out of time. The problem is that we don’t have sufficient compromise all around to be able to close a deal.”

Why States Can’t Agree

The basin is divided into two camps: the Upper Basin states (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico) and the Lower Basin states (Arizona, California, Nevada). The core dispute is straightforward but deeply entrenched: who bears the pain of water cuts in dry years, and how much.

Colorado’s top negotiator Becky Mitchell captured the frustration from the upstream perspective, saying, “We’re being asked to solve a problem we didn’t create with water we don’t have.”

Arizona’s negotiator, Tom Buschatzke, argued his state has proposed creative solutions that “virtually all have been rejected.” Nevada’s lead John Entsminger put it plainly: “Countless nights and weekends away from my family trying to craft a reasonable, mutually acceptable solution only to be confronted by the same tired rhetoric.”

The arguments have been playing out, mostly unchanged, since 2023. Hamby, who has kept detailed notebooks since the negotiations began, flipped through pages of meeting notes reflecting the same positions repeated over three years.

What Happens If States Can’t Agree?

If the states cannot produce a joint plan before the existing rules expire, the federal government, specifically the Department of the Interior, will step in to manage the river under its own authority. The Interior Department has already outlined five potential management options it could impose unilaterally.

The problem is that even the federal government’s own analysis suggests that managing the river under existing authority, without state cooperation, leads to further reservoir decline and serious downstream economic damage. To pursue more aggressive conservation tools, such as innovative water pooling arrangements or deeper cuts, the Interior Department needs state support and likely new legal authority.

The federal authority structure is also complicated. In the Upper Basin, an interstate commission, not the federal government, manages whether states must cut back to meet water-sharing obligations. In the Lower Basin, the Secretary of the Interior acts as the “water master,” holding direct authority over cuts in Arizona, California, and Nevada. The 30 tribal nations in the basin add another layer, with legal agreements and trust responsibilities that create separate obligations for the federal government regardless of what the states negotiate.

Legal challenges are considered likely regardless of which path is chosen. Water experts say litigation is not a question of if, but when and over what.

What This Means for Water Managers and Contractors

The immediate consequence of continued deadlock is uncertainty, and in the water business, uncertainty is expensive. Communities, agricultural operations, utilities, and municipalities across the West are trying to plan infrastructure investments, irrigation systems, and long-term water budgets without knowing what the rules will be in six months.

For irrigation contractors, the signal is clear: efficiency is no longer optional. In a basin where every state is arguing over fractions of a limited supply, water that is wasted through inefficient irrigation systems, outdated controllers, or poor scheduling is water that will increasingly come under scrutiny and may also be subject to regulation.

Smart irrigation technology, including weather-based controllers, soil moisture sensors, and precision scheduling, has always made economic sense. In a Colorado River Basin facing mandatory cuts and federal oversight, it becomes a matter of compliance and competitiveness. Properties and operations that can demonstrate measurable water efficiency will be better positioned regardless of how the regulatory landscape shifts.

The Clock Is Still Running

The basin states were supposed to signal a high-level agreement in November. They didn’t. Then they missed February 14. The next window for meaningful progress narrows with each passing week as the fall expiration of the current rules approaches.

What comes next — federal imposition, state compromise, court battles, or some combination of all three — will reshape water management in the American West for a generation. The one certainty is that the days of treating Colorado River water as an unlimited resource are long gone.

For everyone in the water industry, this is not background noise. It’s the story of where your water comes from, how much will be available, and what it will cost to use it. Paying attention now and investing in efficiency before regulations force the issue is the only smart approach.