If you live or work in the western U.S., you’ve heard the same refrain lately: “We’ve had a lot of rain—are we out of the drought?” It’s an understandable question. Stormy weeks refill creeks, turn hillsides green, and make reservoirs look healthier. In parts of the West, recent precipitation has helped. In California, for example, officials noted that rainfall has been “sufficient” and reservoir storage has been above average, even as they’ve warned that the snowpack matters just as much and that early-season snow has lagged behind.

That last point is the heart of the issue: water security in the West isn’t determined by a single season or year of rainfall. It’s determined by where the water falls, when it falls, how it is stored, and what deficits have built up over multiple years. A single wet year can be a huge relief. But it rarely “solves” drought on its own.

Rainfall Headlines Miss the Real Water Bank: Snow, Soil, and Storage

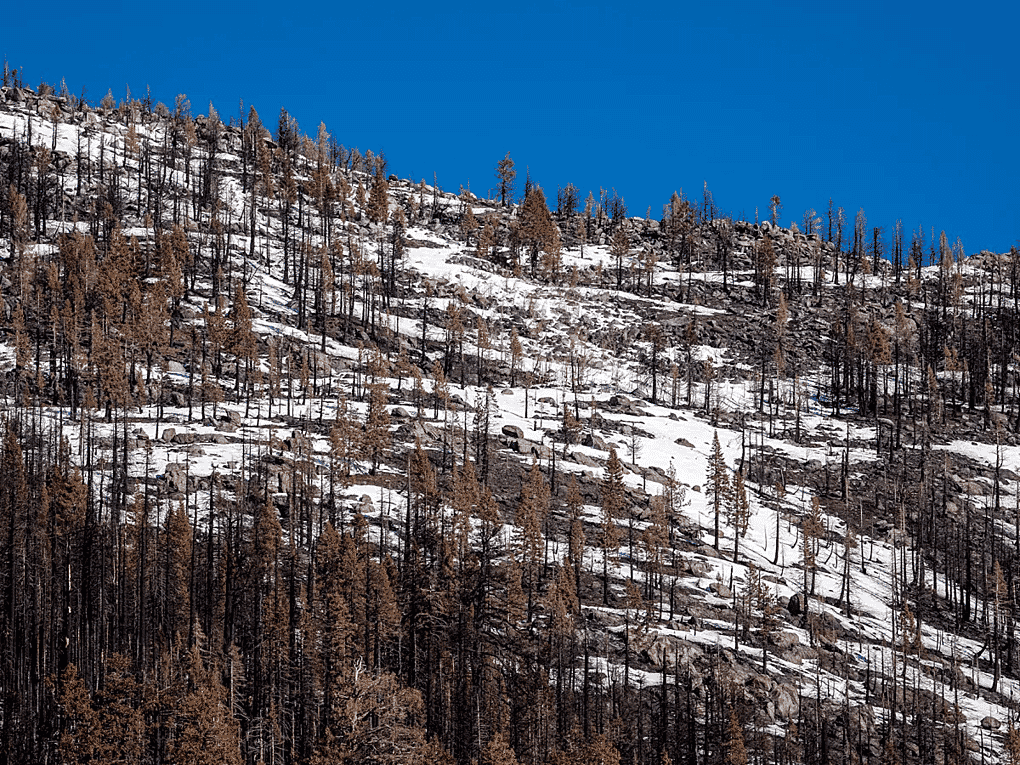

In much of the West, snowpack is the slow-release savings account. Rain is immediate: it runs off quickly, can cause flooding, and is difficult to capture if it arrives in intense bursts. Snow, in contrast, stores water at elevation and releases it over months as temperatures warm, feeding rivers and reservoirs during the dry season.

That’s why even in a rainy period, water managers keep pointing back to snow. California water officials recently highlighted that while reservoirs were in good shape, snowpack was significantly lower than the year before an important concern because snowmelt provides roughly a third of the state’s water in many years. NOAA and partners also track “snow drought” conditions across the West using snow water equivalent data, because low snowpack can quietly set up a dry summer even when winter storms felt active.

Now add the soil to the equation. After a multi-year dry period, the ground behaves like a sponge that’s been left out in the sun. The first storms often go to “paying back” soil moisture deficits and refilling dry shallow groundwater before they generate meaningful runoff into streams and reservoirs. That’s one reason you can have a wet winter and still see limited long-term recovery.

The Hidden Deficit: Groundwater Doesn’t Refill on a Stormy Weekend

When people think of drought recovery, they picture reservoirs rising. But the West’s deeper water story is often groundwater. In many basins, groundwater was used heavily during drought years to keep cities, farms, and landscapes functioning. And groundwater recharge is slow. It requires sustained wet conditions, favorable temperatures, appropriate soils, and often dedicated recharge projects.

This is why water professionals talk about multi-year recovery. One wet year may stabilize conditions and reduce pumping. But it usually doesn’t restore depleted aquifers to their pre-drought levels.

The Colorado River Reality: Big Systems Recover Slowly

If you want a case study in why “one year of rain” isn’t enough, look at the Colorado River system. The Colorado is influenced by snowpack and runoff across multiple states, plus decades of structural over-allocation. Even with improved hydrology in a given year, the reservoirs are so large—and the deficits have been so persistent—that recovery requires multiple years of above-average inflows paired with demand reductions.

Federal projections and operational updates for Lake Powell and Lake Mead emphasize these ongoing constraints and the tiered, reservoir-elevation-based operations. In other words: large systems don’t “snap back” quickly. They respond slowly. Its ike turning a cargo ship, not a speedboat.

Why a Multi-Year View Is the Only Honest View

A multi-year view matters because it captures realities that single-year rainfall totals can hide:

- Hydrologic whiplash is normal now. The West can swing from very wet periods to very dry periods quickly. Seasonal outlooks and drought monitoring tools reflect that drought can persist in some regions even while others improve.

- Timing matters more than totals. A year can look “wet” on paper, but if storms come warmer (more rain, less snow), arrive too fast to store, or hit the wrong watersheds, the long-term benefit is smaller.

- Deficits accumulate quietly. Soil moisture loss, groundwater depletion, and reservoir drawdowns create “water debt.” One year of good deposits helps—but doesn’t erase years of withdrawals.

- Demand doesn’t pause. Population, landscapes, agriculture, and industry keep using water, so recovery must outpace ongoing use, not just match it.

What It Actually Takes to “Catch Up”

So what does real catch-up look like? Typically, it’s some combination of:

- Two to five years of above-average snowpack and runoff in key basins, not just one rainy winter. (The exact number depends on the severity and duration of the prior drought.)

- Stable reservoir carryover—meaning reservoirs not only refill, but hold enough storage to withstand the next dry year.

- Reduced groundwater pumping plus intentional recharge, allowing aquifers time to rebuild.

- Efficiency that becomes permanent, not temporary. The West makes the biggest gains when conservation measures stick through wet years, not just dry ones.

- Diversified supply, recycling, stormwater capture, and (in some places) desalination, so the system is less dependent on one source type.

The Practical Takeaway

The West can and should celebrate rain when it arrives. It reduces immediate stress, supports ecosystems, and can improve near-term supply. But rainfall is not the finish line. The finish line is a multi-year recovery across snowpack, reservoirs, soil moisture, and groundwater, and the operational stability to handle the next dry cycle.

If you want a simple line to use in conversation, here it is:

“A wet year helps. A multi-year pattern heals.”

And the clearest sign of healing isn’t just green hills in February—it’s healthy snowpack into spring, stable reservoir carryover into late summer, and reduced reliance on groundwater year after year.